- Are governments to blame for illegal logging and uncontrolled deforestation?

- Can more be done to combat deforestation?

In this blog post I will focus my attention once again on the country of Brazil and examine the influence of politics on deforestation.

"I used to worry that all the trees in the jungle would be cut down to make paper for their reports on how to save the rainforest" - Nick Birch (1993)

A Brief History of Politics in Brazil

In a pre-colonial setting of spears and campfires, and indeed during colonization, the people living within the verdant countryside of Amazonia valued the forests and appreciated their beauty. Wood was harvested but wisely and used for core practices such as shelter and fire.

Following independence the Brazilian government gave away large portions of land to small-scale farmers as long as they used it "productively" (Chaurahha 2013). This meant tax holidays and government incentives led to deforestation and the expansion of cattle ranches. The money used from the government was put into deforesting more trees rather than the careful management of the land ranch owners had acquired.

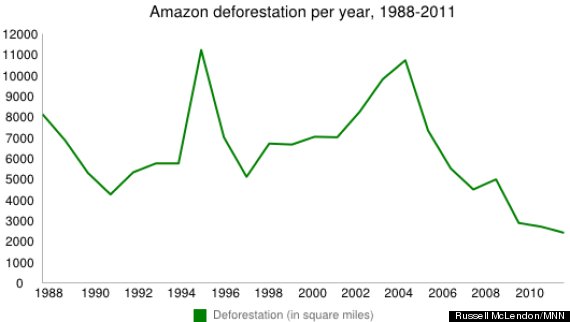

Deforestation peaked in the 1980s when it became clear that the forest was only marketable once the trees had been removed. As Moran (1994) interestingly notes the price of beef did not decline in Brazil despite an expansion of cattle ranches because the money from selling off the land was more profitable for small-scale farmers than the actual cattle rearing.

By 1988 the first environmental impact assessments were undertaken and under Article 26 of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution, the destruction of the Amazon and Atlantic forests were a crime. As both Chaurahha and Moran note, the law was rarely enforced.

Furthermore the construction of the Trans-Amazon Highway (no longer functioning) opened up previously inaccessible portions of the jungle to small-scale farmers and logging companies (Butler Rhett 2012). I have already discussed how the development of infrastructure causes deforestation in "The Future of our Trees". Deforestation moved from the periphery of the Amazon to its core.

|

| Journey to the Center of the Amazon - the Trans-Amazon Highway built in 1972 (source) |

Following a move from a dictatorship to democracy and international pressure Brazil adopted the REDD initiative with which it receives $21 billion to maintain the Amazon jungle. However, this transition to a more democratic government did little for the environment when in 2008 Marina Silva (the then environment minister) resigned due to pressure from powers of economic interest when she argued against the exploitation of the Amazon (NY Times 2008)

Discussion

The two historical accounts by Moran and the blogger "Chaurahha" combined provide a definitive and complementary account of government led initiatives that accelerated deforestation within the 1970s and 1980s before more environmental policies were adopted. The environment and the political are entwined particularly in the Amazon which receives a significant amount of media attention (Hurrell 1991). I think it is ultimately international pressure and public opinion that drives the Brazilian government to combat deforestation after decades of almost promoting it. Furthermore, keeping the rainforest has become profitable for the government under the REDD+ initiative which means the government receives money for maintaining the rainforest (Hecht 2012) - see COP21 post for more details on REDD+. I would agree with Hecht that providing an incentive for maintaining valuable rainforests is key to low income countries understanding the value of the landscape. Supportive of this is Peter Dauvergne's (1994) work into politics and deforestation in Indonesia showed that the government saw the trees as a waste of space on potentially profitable land but once their eyes were opened to the value of keeping the trees attitudes towards palm oil production and logging changed.

The fate of the environment in Brazil (and other countries) comes down to a complex, ever changing and impossible to understand politics (Hecht 2012). It comes down to money pure and simple so the profit of keeping trees must outweigh the profit of cutting them down in rainforests are to be maintained. In a bottom-up approach to analyzing politics through the perspective of environmental groups, Lemos and Roberts (2008) found that the success of the environmental group (with international connections and resources) was always outweighed by developmentalist interests - a process of money making and urban expansion. Furthermore, in a country where millions of people live in favelas why would the government care about the environment when there is humanitarian work to be undertaken?