In the second part of this post I will be exploring why we should be stopping deforestation/why are the trees important? and whether we can achieve such as thing as "sustainable deforestation"? Once again, I will be drawing upon past blogs as well as new academic literature.

I would love to hear your opinion - you can comment on the post or vote in the POLL at the top left of the blog.

Why We Should Stop Deforestation?

From the dark Gothic forests rolling across Siberia to the Kapok trees with their mighty buttresses in Amazonia, trees provide an irreplaceable beauty that is destroyed by deforestation. No academic study can quantify (or qualify) the uniqueness and brilliance of the natural world held within the planet's forests.

With 70% of the world's land species living in forest biomes, deforestation is an ecological threat. Many of the world's endangered species are threatened with habitat loss due to deforestation:

- The Javan Rhino has been reduced to 60 left in the wild because of the conversion of natural forest to farmland (Fernando et al. 2006).

- Bornean Orangutan is critically endangered due to habitat destruction caused by illegal logging (Curran et al. 2004).

- Golden Lion Tamarin is endemic to the Amazon jungle but is endangered due to agriculture and logging (Keirulff and Rylunds 2003).

|

| Hear Me Roar! A Golden Lion Tamarin with her offspring in the Amazon (Rainforest Alliance) |

Furthermore, as I have mentioned already the natural and the anthropogenic world are consistently interlinked and the destruction of forests would have more than an environmental/ecologically impact but also a human one. Plants and animals provide food, medicine and fuel for indigenous communities and less developed nations around the world and removing this vital resource would limit economic growth (Butler 2012). However, as I pointed out with the case study of Madagascar sometimes local communities exploit the rainforest as much as the developed world to the extent that they see the forest as a source of income rather than a resource to be appreciated. 25% of global medicines are derived from plants found in the world's forests (Kirkman 2014). What would happen if these were no longer available? What about medicines for diseases we have yet to discover?

From a purely ecological/environmental perspective deforestation is dark and evil like the ace of spades. It degrades the environment irreversibly and results in the extinction of priceless plants and animals. However, Part 1 showed that deforestation is crucial for human survival so can we reach a compromise?

Can We Achieve "Sustainable Deforestation"?

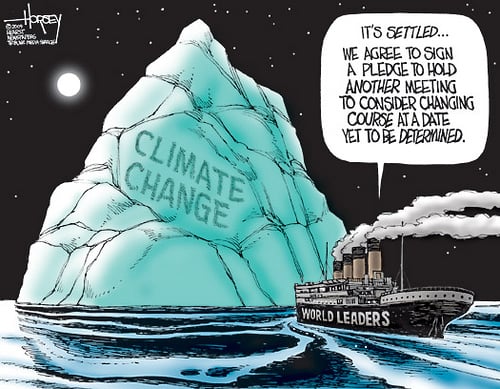

|

| David Horsey's "Environment and Climate" cartoons sum up environmental politics nicely (source) |

However, there are real questions about whether this can be achieved or are we heading for a "tree apocalypse"?

I have talked extensively about corruption and problems with political motivation in Brazil and Indonesia but it also goes down to a smaller bureaucratic level. Particularly in developing countries, departments concerned with forestry, agriculture, water, town planning and land use fail to interact ad often work in isolation with a detrimental effect on the environment as each pursues their own aims. Bawar and Siedler (2015) found this to be the case in the Eastern Himalayas where forest conservationist, land-use departments and small-holder farmers failed to interact to address problems associated with deforestation. What about developed nations? How do we manage the bureaucracy and political motivations there? However, education is key in many respects, as illustrated in the Madagascar case study (Dauvergne 1994). Showing local people, as well as governments, the value in preserving forests and the detrimental effects that will happen if deforestation continues is effective if you show how their actions will adversity effect their lives, and the lives of their children.

Furthermore, a focus on development goals, infrastructural improvements and improving quality of life within countries such as Brazil or Indonesia has put environmental issues on the sideline, in the case of Brazil increased them (Ferraira et al.2014). This paper in Science noted how Brazil's natural resource extraction had increased due to development/urbanization and their growing economy.

We can never fully replace the trees that we have already chopped down, but afforestation and reforestation (discussed on this blog post quite extensively) offers a way to partially restore habitats as well as continue to provide a carbon sink and mitigate against climate change. However, a solution such as this would only be effective if all countries where to monitor deforestation (something that is arguably hard to do) and plant trees to replace the ones that had been felled.

A Conclusion

So that I don't loose track of my conclusions I am going to display them as concise points:

- Whether we like it or not, humans require natural resources (such as wood) to grow and survive and maintain a quality of life that we take for granted.

- Indigenous people have a right to fell trees and make a living off the land in which they live but at the same time should be educated on the negative impacts deforestation will have on their community and the world.

- We must learn from the mistakes of past societies (e.g. the Maya) so that we don't repeat them. Although our considerable technological advancements would mean total societal collapse due to deforestation is unlikely.

- Illegal logging and deforestation is very wrong and tougher penalties should be enforced on those that do not abide by the law.

- As individuals we can purchase environmentally sustainable products so as not to fuel illegal or unsustainable forestry practices.

- Deforestation practices need to be altered in order to meet a growing population or population policies must be implemented in order to ensure we have an adequate amount of natural resources.

- Deforestation can be managed and mitigated in a way that saves endangered species and precious habitats but also provides humans with a source of wood.

- Deforestation is not a necessary evil but wood is a necessity that humans require. Deforestation is a means by which we get this necessity. However, it can be undertaken in a more environmentally friendly way. We can manage and not waste the natural resources we have at our disposal (e.g. slash and burn methods are extremely wasteful or plant fast growing trees that we can then cut down).

Deforestation is a complicated topic that has been explored within this blog. It is implicated within sensitive issues (e.g. population) and complicated ones (e.g. politics) but it is a very real environmental problem that needs addressing. I will also post the results of the Twitter Poll ("Is deforestation a necessary evil?") once it has closed in 17 hours time. The poll on the side of this blog is open until noon on the 13th January so keep voting!

Thanks to everyone who has commented and read this blog over the past few months. I hope you have enjoyed reading it as much as I have enjoyed writing and investigating deforestation.

|

| A cattle ranch in Mato Grosso, Brazil - was it really worth cutting down all those trees? (WSJ) |